A series of newspaper articles published during the week of the

Seaham Colliery Disaster of Wednesday 8th of September 1880.

Newspaper not known.

TERRIBLE COLLIERY EXPLOSION

WEDNESDAY, 10 PM.

A disaster which seems to be of appalling magnitude occurred this morning at Seaham Colliery, Durham, the property of the Marquis of Londonderry. About 2 o’clock there was a loud report, followed by an upheaval of dust and smoke, mingled with shrieks, from the pit shaft. Those above ground could not fail to understand that some great disaster had occurred, but they were not prepared for a calamity of the extent which an examination, of the workings disclosed. The manager, Mr. Stratton, was at once communicated with, and relief parties were formed to descend the shaft.

It was found that the cages were useless, and the explorers were let down by means of loops. It was known that some 200 men and boys had gone into the workings for the night shift at the usual time, the number having been increased beyond what bad been usual by the fact that numbers of the miners intended to work out the usual shift in order to enable them to attend a local flower show to be held today. Three times was an attempt made to reach the entombed men, and three times was failure the result.

On a fourth attempt the exploring party got near enough to the main seam to discover that the men employed there were alive, and further discoveries revealed the welcome fact that they were unhurt. Unhappily, there were only some 17 men in this part of the workings, the greater number being in the more fatally-situated seams lower down.

Efforts were now directed towards getting the lifting gear into working order, so that the men reached could be rescued. This proved a work of great difficulty, and it was long before any progress was made. The afternoon was well advanced before any success was achieved. By about 2 o’clock communication by means of a jack-rope and loops was established, and three men were brought to bank alive. In the course of an hour or two, three others were brought up, and when the latest intelligence to hand here left, efforts wore being made to reach the remaining 11 or 12 men in that seam. They are said to be unhurt. None of the men brought to bank seemed any the worse for their temporary confinement, although naturally alarmed and shaken. Refreshments had been sent down to them, and they waited patiently till their turn came to be taken up.

One of the rescued stated that 40 men in the Harvey, or No. 2 seam, a seam below the main seam, were safe, but it is not stated how he arrived at that conclusion. It is presumed there may have been communication between the seams. It was supposed this afternoon that no fewer than 60 of the 200 men and boys believed to be below would be saved. When the men in the main seam heard the explosion they rushed to the entrance, but found it blocked. The news of the accident drew great crowds during the day to the scene of the disaster.

The manager, Mr. Scrafton, states that the seams worked were the Hutton seam, at a depth of 280 fathoms, and the seam worked from No. 1, which is 256 fathoms. The upcast works three seams, the Hutton seam, the Maudlin, and the Main Coal. The only seam explored is the Main Coal, and ventilation in it when Mr. Stratton went down was perfectly good. He said, “The men there cannot be suffering any harm. Communication has not yet been opened with the other seams, and that will be the principal work that will have to be done.” As near as can be ascertained at the time of writing there would be 33 men in No. 2 pit, 35 in No. 1, 60 in the Maudlin, 19 in the Main Coal, and 17 in No. 3, Hutton seam – a total of 164. Of these, 19 in the main seam are safe and the men in No. 2 will probably be safe unless the pit is fired, I cannot speak as to the others. While down, voices and knockings were heard in No. 3.

Messrs. Forman and Patterson, president and treasurer respectively of the Durham Miners’ Association, have been at the colliery during the day, and have arranged for two other representatives to accompany each exploring party. On behalf of the men Messrs. Patterson and Burt will go with the first shift, Messrs. Crosier and Forman with the second, and Mr. James Wilson and Mr. Banks with the third. Corporal Hudson, who won the Queen’s Prize at Shoeburyness, is among the men in the lowest seam, as to whom there is least hope. He was to receive his prizes today from the Marchioness of Londonderry. With him is a miner named Hutchinson, who was saved in a miraculous manner at an explosion on the 25th of October, 1871, in the same pit. The Marquis of Londonderry has been at the pit mouth during the day, and is deeply concerned as to the fate of his men.

The colliery is a very large one, having two shafts and is among the deepest in the country. If the worst fears should be realised, the calamity will be far greater than all accidents that have occurred in this quarter since the terrible disaster at Hartley in 1862, by which upwards of 200 persons lost their lives. The cause of the accident is, of course, unknown. After a fortnight of extreme heat, the weather this morning became cold, with a tendency to frost.

LATER

Those who have been seen dead are near the shaft. Some of the men are believed to be a mile away. It is supposed that the former were overcome by the after-damp. A woman named Featt dropped down dead on being told that her brother was among the victims. Women who may be widowed and children who may be fatherless are waiting drearily in the roadways leading to the colliery. In all 67 hands have been saved, though some of them are in a very exhausted state. The work of the explorers is very difficult, but they will continue it all night, and it is hoped that they will affect a clear way into the workings by morning. No signs of fire are perceptible, though there must be a large accumulation of gas in the pit.

ANOTHER ACCOUNT , SEAHAM HARBOUR,

WEDNESDAY NIGHT

Early this morning a terrible explosion occurred at Seaham Colliery, belonging to the Marquis of Londonderry, and situated on a hill about a mile from the sea and within sight of Sunderland. There was to have been a flower show at Seaham Harbour to-day, and the prizes were to be given away by the Marquis of Londonderry. The pitmen of the colliery have large gardens attached to their well-built houses and are keen competitors for prizes. The explosion occurred at half-past 2 o’clock this morning, and was heard between two and three miles off.

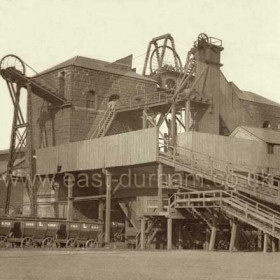

The Marquis of Londonderry was at one of his seats, within half a mile of the pit, Seaham Hall. He was soon on the spot, and has remained here all day. There was no want of assistance, as colliery managers and owners from all parts of the county flocked in. Mr. Bell the Government inspector for Durham, and his assistant, Mr. Atkinson, also appeared. The Seaham colliery was sunk about 40 years ago, and was worked about half that time with a single shaft for sending down the men and ventilating the pit. This system of working was abolished by the Mines Regulation Act of 1862, which made it compulsory to have two separate and distinct shafts, some distance apart, for ventilation and taking the men up and down the pit.

The Seaham Colliery is now worked with the old arrangement of a shaft with a brattice separating it, but this is now entirely worked as a downcast shaft, where the men go down and come up, and this is called No. 1 and No. 2 shafts—really one shaft with a brattice up the centre. The upcast shaft is about 150 yards away, and there is the place whence all the foul air comes from the pit. There are five seams of coal being worked, the main seam 460 yards from the surface, where 17 men have been rescued; then the Maudlin seam, 490 yards, with 60 men and Nos. 1, 2, and 3 Hutton seams, with 55, 33, and 17 men respectively working, making a total of 162 down the pit at the time of the explosion.

Those seams run on an average to between five and six feet and it should be said that the Hutton seams are broken up by a ‘fault’, and are worked in three sections about 20 yards below the main and Maudlin seams. There are two seams further down – the Harvey and Busty – at a depth from the top of the shaft of 500 and 600 yards. There are about 1,000 men employed at the colliery altogether, and they work three ‘shifts’ per day, of seven hours each so that the full complement of men in the pit at one time would not be less than 500. When the explosion occurred there were very few hewers in the pit, the men there being principally engaged in clearing the travelling ways and putting in timber to support the roofs and make it safe for the men to get the coal. The force of the explosion, at present supposed to have originated in the lowest seams, was such as to block up both the upcast and downcast shafts, and this led to the belief that every soul in the pit had perished. Ventilation was, however, soon restored, and the work of removing the debris in the shaft was begun.

The efforts of the exploring party were soon rewarded by sounds from below and within four hours of the explosion, 19 men in the upper or main coal seam were found, all alive and well. They were got at by relays of men going down through the broken and shattered shaft by means of loops slung on chains, the regular cages and runners having been destroyed.

Three men were brought up from this main seam at 1 o’clock, the other 16 having refreshments sent down to them and electing to stay rather than impede the party in their efforts to rescue the sufferers who had been heard knocking and shouting further down the shaft. The latter, it is hoped, will be reached in the course of a few hours, for at present the ventilation is not bad. There is a large volume of air proceeding down the downcast but whether it goes down to the four lower seams before reaching the upcast is not known. There, 165 men are still imprisoned. The knockings from down below, however, indicate that some men still survive, and it is to rescue these men that the 16 brave men in the main seam prefer to remain immured rather than stop for a few minutes the work of rescuing their less fortunate comrades. Four men were brought to bank later on, and at half-past 6 o’clock the news was brought up that several men had been found alive in the Hutton seam, No. 1 pit, where 55 men were known to have been working.

At 1 o’clock the exploring party, which had up to this time been using only the No. 1 and No. 2 downcast shaft, also got to work in the upcast shaft, and this enabled them to proceed at a much greater rate. An hour later six men were brought up to bank, and there are 15 more waiting their turn to be sent to the surface. The furnace man at the bottom of this upcast shaft was found dead, and there are some others also fearfully burnt near the furnace. It is feared that 140 men and boys are killed.

The Marquis of Londonderry has been most solicitous in behalf of the sufferers, and has been about the colliery all day. Sir George Elliot, who was formerly consulting engineer to the Marquis, has offered his services, and sent some of his own managers from adjoining collieries. The most eminent colliery managers and engineers in Durham have been in attendance during the day, among others, Mr. S. Coxon Usworth, Mr. Baker Forster, Mr. William Armstrong, Mr. Morton (Lord Durham’s agent), Mr. C. E. Bell, Mr. Morison (Newcastle), Mr. A. L Stevenson, Mr. Bailes (Murton Colliery), and Mr. Lishman (Hetton). These gentlemen gave their counsel to the resident officials of the colliery, Messrs. Edminson, Stratton, Corbett, and Turnbull, whose exertions have been unremitting during the whole day. Thousands of people continue to flock into the village from neighbouring collieries.

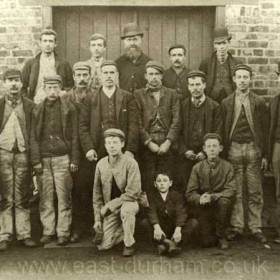

The following is a narrative of one of the men, Ralph Marley, who was immured with 13 others in the main coal seam. He said:-

There was a set of four of them working together, 1,200 yards from the shaft, driving and heading a work preparatory to the hewers getting the coal. Here they used powder for bringing the stone down. They always took the precaution to go 80 yards in different directions to see if gas was to be found, but so free is the colliery from gas that during the twelve months he had been working in the seam he had never seen gas. Lamps of the most approved pattern, the Belgian, Davy, and Stephenson, are used all over the pit, although no gas is ever seen, and the current in the main drivings is so strong that the men have to keep their eyes partly closed to keep out the dust caused by the rush of air.

Marley said that about 20 minutes past 2 o’clock they felt a rush of wind, and he said to one of his mates, ” There’s something up,” and his mate thought there was a fall somewhere near the place, but on looking he found nothing. Marley, who had been in three colliery explosions before, told his mates that the pit had fired, and on their going towards the shaft, about a quarter of a mile from it, they found a deputy overman, named Wardle, lying insensible, with his face covered with blood, and here they met the afterdamp. Up to this time they had fresh air, but on proceeding along towards the shaft they saw the effects of the explosion. Doors had been blown down, and there was debris about the main ways.

When they reached the shaft there were 19 of them, with eight or nine lamps among them, the rest having had theirs blown out at the time of the explosion. They were getting air into their seam, but the return air was so foul that it was like being in a very smoky room. They had water and tea with them, and they partook of this refreshment, but they had misgivings as to whether they were out of danger. They dreaded a second explosion, and they travelled about in different directions in couples to see whether there were any signs of fire, but not finding any, they sat down, now and again shouting up the shaft without, however, getting any response. About 5 o’clock they thought they heard voices from above and this cheered them, but it was not till 1 o’clock that they were assured of being rescued.

Marley, who is an elderly man, was then slung in a loop, and with two others brought to the surface, and walked home, where he has been visited by many relatives. It is nine years since on explosion occurred at this colliery and at that time 28 people were lost.

The Government Inspector telegraphs to the Home Office:-

“I regret to have to report an explosion of gas at Seaham Colliery at 2 o’clock this morning. Two hundred men in the pit. Shafts blocked. Seventeen men saved in an upper seam. Sounds from men below. Plenty of assistance. Work progressing favourably. Hope to get down before night.”

THE SEAHAM COLLIERY EXPLOSION.

Thursday morning

As was fully anticipated, all the miners in the main and Harvey seams – about sixty in number – were rescued by midnight. The damage done by the explosion in throwing the cages in the shaft out of gear, and thus entirely deranging the communication, while giving the strongest evidence of the force of the explosion, formed an insuperable obstacle to communication with the men below for a considerable time. It took full gangs of workmen the greater part of yesterday to get it into anything like order again. The men and boys who were working in the main and Harvey seams are saved and at their homes, some badly hurt, but none likely to succumb to their injuries. But all the poor fellows who were employed at the moment of the explosion in the Hutton and Maudlin seams, roughly stated at about 140 men and lads, are dead.

The explosion undoubtedly occurred in the Hutton seam. The wreckage there is fearful indeed, according to the latest advices, it is believed that the bratticing and woodwork in that part of the mine are on fire. The horses and ponies employed in the mine, about 250, are dead. They have either been killed by the explosion or suffocated. The mine is a fiery one, and there is no doubt the explosion originated in a ‘blower’ of gas coming away from a crevice somewhere in the face of the workings in the Hutton seam. The Seaham Colliery has been long wrought, and, as is usual in mines which have been in use some time, there is sure to be a good deal of ‘goof’, or wrought-out workings. Gases generally lurk about in them. In the normal condition of the mine they are innocuous; but in an explosion like that of yesterday they would add to its force

The explorers have been able to get as far as the staples in the Maudlin No. 3 pit; but they there encountered a heavy fall of stones, and their progress was thus stopped. Great patience will have to be exercised in the exploration of the mine. All that human courage on the part of the viewers and miners, not only of the colliery, but of the entire north-east section of the country, could do, has been and will be done to fathom the extent of the disaster and to see whether a human being is alive. But they are contending with terrible and treacherous forces. It cannot he guessed when their heroic task will be accomplished, for the actual condition of the mine in all its parts has hardly been determined yet.

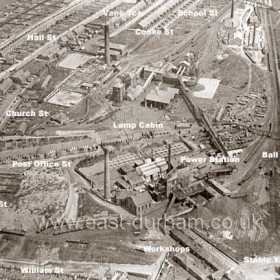

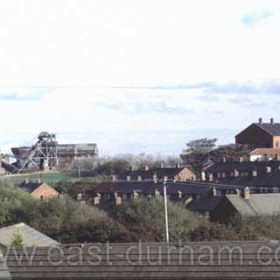

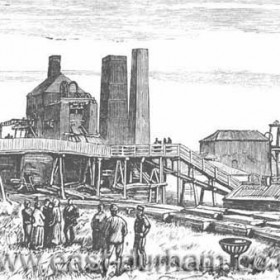

As already reported, Seaham Colliery is situated a few miles to the southward of Sunderland, and is the property of the Marquis of Londonderry. It is one of the largest in the North of England, employing from 1,400 to 1,500 men and lads, with an output, when in full work, of something like 2,500 tons of coal. The product is mainly gas coal. There are two pits, one being called Seaham Colliery and the other Seaton Colliery. The latter bears also the local cognomen of ‘Nicky-Nack’. It is also called ‘the High pit’, Seaham Colliery being in like manner described as ‘the Low pit’.

The shaft of the Low pit is divided by bratticing into two portions called No. 1 pit and No. 2 pit respectively; while Seaton Colliery is No. 3 pit. The Low pit is the downcast of the colliery, and the High pit the upcast. There is a communicating drift between these two portions of the colliery, so that in case of danger the miners may have more than one line of retreat. The shafts give access to four seams of coal – the main seam, the Maudlin, the Hutton, and the Harvey; this being the order in which they lie from the surface. It is the Hutton seam chiefly which is worked, and there is but little done in the Harvey, which is the lowest of the series.

The explosion occurred shortly after 2 o’clock yesterday morning, and it must have been of an unusually violent character, for it was heard not only at Seaham Harbour, a mile and a half from the pit, but also at sea, in the offing. Perhaps from this circumstance, it is generally believed to have happened at or about that portion of the mine which lies immediately under the sea-shore. Those who were about at the time say there was a loud report from both pits simultaneously, followed by a dense volume of smoke, dust, and sparks. There was a sensible shaking of the ground in the neighbourhood of the pit, and sleepers in the village ware awakened.

So soon as the state of the shafts could be examined it was found that the force of the explosion had so damaged or destroyed the cages and their fittings in the different shafts that access to the mine was completely blocked. In Nos. 1 and 2 of the Low pit the guides were broken away and the cages forced upward in such a manner as to cause a stoppage, while in the High pit a similar state of things prevailed, the wire ropes used to guide the cages being blown and twisted about to a very remarkable extent. The first thing to be done, therefore, was to clear away this wreckage as far as possible in the shafts, and thus make way for the descent of exploring parties. There were hundreds of volunteers on the spot, both from the ranks of working miners and from the colliery engineers connected with the different mines in the county.

After several hours of anxious exertion one of the shafts was so far cleared that explorers were able to descend in loops of rope, and were able to communicate to those at the bank the intelligence that the 10 men in the main seam were at any rate safe. About 1 o’clock in the afternoon some of these were rescued, and three brought to the surface. The engineers then proceeded to rig up a cradle in order to bring up the others, and about 4 o’clock they had conveyed to them from below the gratifying news that the 40 men in the Harvey seam were also safe. Those were brought to bank before midnight at the High pit.

Up to a late hour there had been no access to the other seams the Maudlin and the Hutton. Unhappily it was in these seams that most of the miners were at work. Every preparation had been made so that any of the men requiring medical aid might be attended to at once. Everyone engaged in the exploration of the mine or in working in any capacity about the pit, laboured most assiduously. The officials, among whom are Mr. Corbett, managing viewer to Lord Londonderry, Mr. Stratton, manager at the pit; Mr. Turnbull, viewer, Mr. Rowell, engineer, and others, were all at the scene of the accident, superintending arrangements and devising the best means possible to open out the pit and rescue the men. There were also mining engineers from all parts of the county, including Messrs. Hall, Ryhope; Parrington, Monkwearmouth; Armstrong, Wingate; Lishman, Hetton; Lishman, Bunker’s Hill; Bailes, sen. and jun., Murton; Armstrong, Pelaw-House; and others.

What was wanted was a plan by which their services could be made available. The difficulty offered in Nos. 1 and 2 pits was the fixing of the cage by the breaking of the bratticing below the main seam. After investigation, however, it was found that a way could be found to the bottom of the shaft of Nos. 1 and 2 pits by means of a tunnel which connects the Nos. 1 and 2 or Low pit with the High pit. The exploring parties, who were sent down the former, having found their way into the latter by means of the tunnel, were lowered in ‘kibbles’ to a passage which led them again into the main seam at the lower pit shaft. By this circuitous route some of the 19 men in the main seam were raised to the surface

It was with difficulty that the men could work at the High pit shaft owing to the dense clouds of smoke which constantly rose up from below. But it was necessary that this shaft should be cleared in order that communication with the seams below the main seam might be effected. This being the upcast shaft, the heat here is always so great that the cages and their fixings are all of metal When the explosion occurred its force warped the wire ropes which acted as guides to the cages when they were being raised and lowered. This caused a block in the shaft, and it was only by a great amount of patient labour that it was made perfectly clear. The course adopted was to pull up the eight guide-ropes of the cages, and as the latter would be of no use after the ropes were gone it was also decided that one of the cages should be removed from the shaft.

For several hours the work of removing the guiding ropes proceeded. When the guides had been taken away, the removal of one of the cages out of the shaft was begun, and proved to be a work of difficulty. It was accomplished shortly after 4 o’clock. The High pit shaft was now clear from the top to the very bottom, giving free communication with all the seams. A ‘kibble’, or tub, was lowered by means of the ordinary cage rope down the pit, and on reaching each seam hung awhile in order that any men there might have an opportunity of getting into it.’

The ‘kibble’ was lowered as far as it could go, and remained below a long time, the men at the top listening for signals.

About 6 o’clock Mr Stratton, in charge of an exploring party, decided to descend the High shaft, in spite of the smoke which it was emitting. A few minutes after this had been decided upon, upwards of 100 miners, provided with lamps and every necessary for exploring parties, arrived to go down. Each party, which consisted of from eight to ten men, had two Queen fire-engines, to be used if necessary upon the fire that was believed to be raging in one of the seams.

After having been down the shaft for fully half an hour with the exploring party, the kibble was sent to bank with William Laverick, an onsetter in the Harvey seam. This poor fellow had suffered terribly from the explosion. When he was brought to bank an involuntary expression of pity burst from the onlookers. His face and head were swollen to an enormous size; his eyes were not visible. The hair of his face and head had been scorched off. It was proposed that he should be carried to his home, but in a perfectly firm voice he said that if he were steadied just a little he could walk well enough. He was led away, and was afterwards attended to by Dr. Baty and Dr Crosby. The next to be drawn to bank were William Morris and Jacob Steel, both of whom displayed signs of exhaustion.

The scene at the mouth of the shaft was now a curious one. Darkness had set in, and the shed over the pit was lighted with two or three gas lamps, which threw only a dim light around. Within the shed a way was left between the mouth of the pit and the engine-house adjoining, in order that instructions shouted to the engineman might be heard with distinctness by him. Holding a chain with one hand for a support, a young miner was lying on his side, with his head and shoulders hanging over the mouth of the pit, listening for signals from below.

George Thompson, who was raised to bank from the main seam at 1o’clock, gave the following account of the occurrence:—

“About half – past 2 o’clock I and about 18 others were working in the main seam when the explosion occurred. Several of the men in the seam heard the noise, but I and others did not hear it. We all, however, smelt gas. It quickly flashed upon our minds what had occurred, and for a time we were in a state of great excitement. We found after a while that we were safe if those at bank would only send down to us. We spent the time during which we had to wait for help in walking backwards and forwards along the seam.

We were all uninjured except Robert Wardle, who when in the ‘stapple’ was much bruised by a piece of timber which was blown on to him, I could not tell for some time after the explosion what was being done in the seam, as I was in a state only of semi-consciousness owing to the gases.

There was a plentiful supply of water, and there was some food among us. This, together with the light from several of the lamps which had not been blown out, rendered our situation less uncomfortable than it otherwise could have been. We heard the men in the Harvey seam shouting, but we could not make out what they were saying, and we shouted in return. I cannot express to you the joy we all felt when the exploring party brought us assurances of our safety and rescued us from our terrifying position.”

Alexander Kent, shiftsman in the Harvey seam, gives the following account of what befell him and his companions:-

“I was in the extreme end of the cross cuts in the Harvey seam, working in company with another man named Gatenby, taking down stone and timber. About bait time – 20 minutes or half-past 2 o’clock – we both came out of the place in which we were working into the main wagon-way. On doing so we noticed a thick dust, and, suspecting something serious had happened, we continued on towards the shaft. Nothing worse was observed at this part, but the further we proceeded the thicker the dust and smoke became. We still proceeded on past the engine plane, about 500 or 600 yards from where we were working. After we had passed the engine plane about 100 yards there was a smell of fire. As we got nearer to the shaft the smell got stronger, and the smoke thicker. Passing the old route way the smoke was lighter, but there was still a strong smell of burning and smoke.

We came on to the Harvey shaft bottom, and here found about 30 other men who had made their way to the same part. A portion of us came up the steam drift from the Harvey seam to No. 1 pit bottom, and then proceeded from No. 1 to No. 4 pit bottom. Not getting any answer to calls which we made up the shaft, we returned down the steam drift to the engine-house, and remained there until 7 o’clock at night. We now got word that communication was open to bank, and that men were being sent up the shaft. We wandered about very much, seeking an opening to get out, but finding there was none we took refuge in the Harvey engine-house, where we remained some hours. We saw a great smoke issuing from the Maudlin seam, but no fire. On our way out we passed three dead bodies, but could not make out who they were.”

Kent was formerly an inspector in the Sunderland Police Force, but left about 10 years ago.

NIGHT

The exploring parties in search of the dead continue to encounter very serious obstacles in working their way towards the part of the mine where the bodies of the unfortunate men and boys are lying. The working parties have fallen in with bodies, and found them frightfully burnt and shrivelled. There is still great difficulty experienced in working the hauling gear, and trouble has been caused below today by a fire which has existed near the stables and engine-room of No. 3 shaft. The viewers and working parties are, however, doing their utmost to reach the scene of the disaster.

ANOTHER ACCOUNT

It is now tolerably certain that about 130 miners have lost their lives. No fewer than 76 women have been widowed and 284 children made fatherless. Considering the terrible extent of the calamity it is wonderful how calmly and patiently the survivors bear the heavy affliction which has befallen them. The efforts of the exploring parties have been carried on with unabated vigour since yesterday morning, each party being relieved at intervals of four hours.

Numbers of bodies nave been discovered, most of them terribly mutilated. They are principally in the Harvey and Maudlin seams, and it is probable that they cannot be brought to bank until a late hour; indeed, several will not be recovered before the end of the week. The first man taken out yesterday states that in making his escape he passed the body of Hall, a furnace-man, lying upon the ventilation fire, where he had evidently been hurled, shovel in hand, by the force of the explosion. He was horribly charred and disfigured. One boy’s head was burnt completely off. The number of horses and ponies below is estimated at more than 400, and all have been killed. It is believed by competent explorers that no one unaccounted for has survived.

A considerable quantity of coal was on fire during the night, but by the use of extincteurs at hand, the flames were virtually subdued this afternoon. The fire was confined mainly to the bulk ends. Canvas ventilators are being plentifully used by the exploring parties, whose efforts are wonderfully successful, the fire being extinguished nearly as far as the stables. At first the obstruction in the shaft of No. 1 pit extended 20 fathoms up the shaft. Late this afternoon this had been reduced to about six feet, and to-night it is expected will be totally cleared. When this is accomplished communication can be opened with the bank.

For some time the water supply was defective, the main seam stable pipes being broken by the force of the explosion. This has now been remedied by supplies from the surface. As was the case yesterday, the Rector has caused frequent services to be held in New Seaham Church, which has been opened throughout each day for private prayers. Hundreds from Sunderland and surrounding villages are visiting the scene of disaster, but admirable order prevails. Subjoined is a list of the killed:-

| Married – Thomas Henson, five children; Robert Dixon; William Robinson, seven; Robert Bawling; Joseph Rawlings, two; Robert Potter, two; Thomas Seavin, three; Thomas Dodson; Thomas Gibson; John Bately; Anthony Scarf, four; Michael Anderson, two; Thomas Patterson, two; John Redshaw; Robert Defty, two; Anthony Smith, four; John Wilkinson; George Wilkinson; William Growns, three; John Growns, three; Thomas Greenwell; Thomas Hayes; T. Hayes, jun.; Benjamin Redshaw, two; Samuel Beiner, eight; John Roper, one; Walter Dawson, six; Robert Haswell; Luke Smith, two; Benjamin Ward, three; Richard Cole, five; George Brown, widower; James Brown, two; William Simpson, three; Frank Watson, one; George Dixon, five; Thomas Shields, three; Thomas Hutchinson, one; Henry Turnbull, one; Joseph Sherball, one; Joseph Sherball, six; Henry Aylesbury; Charles Dawson, four; Joseph Chapman, four; John Wiers, six; Thomas Alexander, eight; Michael Keeney; John Riley; Jacob Fletcher, six; Matthew Charleston, three; James Clarke; Thomas Keenless; Mark Harrison, one; John Denning; William Lamb, two; John Sutherland, 12; William Rosely, three; Edward Johnson, three; Henry Turnbull, six; James Best, six; William Strawbridge; Joseph Waller; Joseph Pinkney, ten; John-Vickers, five; Isaac Ditchleson, eight; Charles Smith, one; John Winter, six; William Morris, one; Robert George, five; Joseph Richardson; W. Wood, three; William Lonsdale and Joseph Burlick. |

| Unmarried – James Healey, boy; John Whitfield, boy; Joseph Waller, boy; Nathan Brown; John Urwin, boy; John Knox, boy; David Knox, boy; Joseph Straughan; John Mason; Silas Scrofton; James Clark, jnr.; Roger Michael and William Henderson; Robert Graham; Edward Pinkett, boy; John M’Guinnes; George Burns, boy; John Cork; Lees Dickson; Thomas Lawson, boy; James Kent, boy; William Wilkinson; John Riley; Joseph Waller; William Hancock, boy; Alfred Turner, boy; William Taylor, boy; James Johnson; John Copeland; John Rainshaw ; Michael Henderson; John Richard Henderson; John Redshaw; Frank Growns; Thomas Johnson; Thomas Hayes; Edward Brown. |

So far as can be ascertained nearly 70 persons have been saved. Riley and Laverick, who are among the number, are injured, the latter being in a most critical state.

Prompt measures have been taken for succouring the bereaved ones, and thanks to the institution of the Northumberland and Durham Miners’ Relief Association, a fund contributed to jointly by masters, and men, the assistance is already at hand The Association has 70,000 members, and an accumulated fund of £80,000; and although this sad affair will be a very heavy drain on its resources it is certain that there will be no appeal to the public.

THE SEAHAM COLLIERY EXPLOSION

Saturday

The number of those actually missing and lost was made up to 164 tonight, and 153 names have been given to the officials of the Miners’ Relief Fund by the relatives.

The sympathy of the people in the neighbourhood is taking practical shape. On Saturday afternoon a preliminary meeting was held at the colliery offices, the Rev Mr. Scott, the Vicar Of Christ Church, who has shown such exemplary liberality throughout, presiding. It was resolved, “That in presence of the widespread calamity that had befallen the people of Seaham Colliery, it is desired that a subscription be set on foot for the relief of the widows and orphans and other relatives dependent upon those who had been lost.”

The vicar said it was time that the relatives of the dead, as members of the Durham and Northumberland Miners Permanent Relief Society, should be relieved from its funds.

Later in the day a public meeting was held at the Mechanics’ Institute, Seaham, the vicar of Seaham Harbour, Mr. Collin occupying the chair. Lord Castlereagh, the eldest son of the Marquis of Londonderry, took occasion to express his father’s sympathy with the poor people, and moved a resolution for the formation of a committee to succour those who had been bereft of their breadwinners. Major Eminson seconded this, and pointed out that those who had been provident enough to subscribe to the relief fund ought to share equally in the money raised by public subscription with those who had not enrolled themselves as members of the society. This was also enforced by Mr. Wright (the Marquis of Londonderry’s solicitor) and Mr. Howie (the chairman of the fund), who said that while their fund was equal to meet this emergency; it might cripple their resources in the future. A committee was then formed, including the Marquis of Londonderry, Lord Castlereagh, and the principal inhabitants of Seaham; and it was resolved to discuss at a future meeting whether the contribution should be handed over to the Miners’ Relief Fund for distribution.

The general opinion expressed, however, was in favour of availing themselves of the miners’ organization. The Bishop of Durham has written to the Rev. Mr. Scott, offering his services in raising subscriptions; and Mr. Burt, MP, and Mr. Macdonald, M.P., have written letters expressive of sympathy from the mining associations that they represent. The Durham Miners’ Association have also sent their condolence, Mr. Pickard, who represents the Lancashire miners, and has been here for two or three days, wishes to state as the result of conversations that Mr. Forman and Mr. Paterson, officials of the Durham Miners’ Association, believe the arrangements for the safe working of the mine to be complete.

Tomorrow Mr, Pickard intends to go down into the pit in order to be able to give evidence at the Coroner’s inquest on Wednesday. This opinion seems to be confirmed by the fact that not a single complaint has been heard as to the ventilation or of lax discipline.

On Saturday afternoon the Home Secretary (Sir William Harcourt) paid a visit to the colliery, in redemption of a pledge given to a deputation of miners who had an interview with the right hon. gentleman at the Home Office with regard to the rules for the prevention of accidents in mines. Sir William then stated that he would consider the suggestions laid before him (the principal one of which was against the use of powder for blasting), together with the report of the Royal Commission on Accidents in Mines, and added that if the opportunity unfortunately presented itself he would personally attend the scene of any disaster in order to become better acquainted with the subject, with a view to further legislation.

Sir William and Lady Harcourt had been staying with the Marchioness of Ripon, at Studley Royal, near Ripon, and the right hon. gentleman had frequent telegrams from Mr. Bell as to how the work is proceeding. Sir William drove from Sunderland, reaching the pit at half-past 1 o’clock, where he was met by Lord Castlereagh; Mr. Stratton, consulting engineer of the colliery; Mr, Bell, the Government inspector for Durham and Mr Willis, the Government inspector for Northumberland. Sir William first proceeded to the drawing office, where he inspected the plans of the workings, and then the party walked to the No. 3 upcast shaft, which is the only one at present by which access can be gained to the mine.

Arriving at the pit mouth the Home Secretary had explained to him the measures that were adopted for the reception of the dead and Sir William had the melancholy satisfaction of seeing the last body brought up that will be sent to the surface for some days, owing to the remainder being so far away from the shaft and the gas being too powerful to admit of further explorations at present. The body proved to be that of Anthony Ramshaw. It was carefully wrapped up in brattice cloth, and the rough miners tenderly carried it on a stretcher, and placed it in a coffin, in which it was conveyed to the poor man’s home. The signal bell again rang, and the word having been given to ‘Bend up’, the kibble disclosed the blackened form of Mr. Stratton, the certificated manager of the mine, who has worked assiduously throughout. He was the first to enter the mine and convey the good news to the men in the upper seam that they were likely to be saved.

Mr, Bell introduced Mr Stratton to the Home Secretary, who complimented the manager on his gallant conduct throughout this sad affair, and then interrogated him as to the state of matters below ground. In reply to the question as to how far the gas was supposed to have accumulated from the bottom of the shaft, Mr Stratton said that the nearest point at which the gas was to be found was 150 yards from the upcast shaft, and was situated in No. 3 Hutton seam, and the other portions of gas lying near the shaft were in No. 1 Hutton seam, about 400 or 500 yards from the upcast shaft. Mr. Stratton also explained that currents of air were circulated between the two shafts, and also between the points where the gas was known to exist, and this was an effectual protection. The quantity of air sent down was l00, 000 cubic feet per minute.

Sir William observed that in the working of extensive coalfields it was desirable to have a number of shafts so as to afford better means of exit when such accidents occur. The Home Secretary asked for information as to the nature of the mine as contrasted with other mines in the neighbourhood; and Mr Bell assured Sir William, after long experience of mines in various parts of the kingdom, and particularly in Lancashire, where dangerous mines exist, that he considered the pits of Durham much more safe than those of any other districts that he knew of, and also that they were better managed, the Home Secretary then asked some questions about this particular mine, and Mr. Bell replied that he considered this one of the dangerous collieries in the County of Durham, on account of the large quantities of gas which it gave out. Sir William then took a look round the appliances at the top of the pit, and walked back again to the colliery offices, where he had half an hour’s conversation with Mr. Bell, Mr. Willis, and Messrs. Eminson, Corbett, and Stratton.

Sir William expressed himself satisfied with what had been done, and wished to convey to the sufferers his heartfelt sympathy with them in their distress. Sir William then returned to Sunderland to take the 3.30 p.m. train for the south. The visit of Sir William is highly appreciated by all the miners in the district, and is looked upon as evidence of his desire to gain information to be used for their benefit in the future. One of the officials, who came to the bank when Sir William was present at the mouth of the pit, communicated the following to the representatives of the Press:-

“No explorations are going on now. We have ceased to explore the cause of the explosion. We know the position of the pit exactly, and we find it unnecessary to go into any further danger. It would only be risking men’s lives. We are confining ourselves now to an examination of the points of danger. We know these dangerous points and we are keeping a constant watch on them, and reports in reference to them are being continually sent up

.

The body of Anthony Ramshaw was found in No. 1 pit, about 500 yards from No. 1 shaft. All the other bodies are in the workings ‘in bye’, and it is impossible to get at them until the whole of the ventilation is restored to the state in which it was before the explosion. Most of the bodies now will be from a mile to two miles in. The ventilation has improved considerably since last night, and at this time the gas has been beaten back to its position at mid-day on Thursday. There is no danger to be apprehended as long as it continues the same. The measures adopted for restoring ventilation will not vary in any way from the present methods until the downcast is opened out to carry the men up and down, and that, at the lowest estimate, will be on Monday afternoon,”

The latest information as to the state of the pit is that the ventilation is improving, and that by tomorrow morning the debris in the downcast shaft will have been cleared away and the ventilation restored in such a manner as to allow of the furnace being lighted to bring the ventilation to its normal state. Owing to the havoc caused by the force of the explosion in the downcast shaft, five men only can get to work, and they are suspended in a loop.

It is anticipated that in a few days the exploration will be resumed, and then some information may be gained as to what is the probable cause of this disaster. One of the frequent causes is the use of powder; but in the seam where the explosion is supposed to have taken place powder is very seldom used, the coal being easy to work. On all hands it is allowed that no expense has been spared to get the newest appliances and to have the very best men in charge of the different sections of the workings.

Today crowds of people began to pour into the village by train and in all sorts of vehicles, and, in addition, many thousands of persons walked long distances, to see the sad spectacle presented of 30 funeral processions to the two nearest churchyards. It was estimated that there were not fewer than 30,000 people in the vicinity of Seaham Colliery Churchyard, where 25 internments took place; and there were also some thousands at the Seaham Harbour Churchyard, which is about a mile and a half from the colliery.

It was a touching scene to see procession after procession arrive at the gates of the Colliery Churchyard, where the vicar, the Rev. Mr. Scott, met them, and addressing a few touching words of encouragement and consolation to those who ware weeping sadly for the lost ones, exhorted them to lead better lives in the presence of this great catastrophe and to give up the gambling habits to which so many of them were addicted.

When the last procession had filed into the churchyard, the coffins were arranged alongside each other, and, the relatives having formed a circle, the rev. gentleman delivered an eloquent address. Fourteen bodies were than placed in a grave near the monument erected to 25 victims to a similar explosion nine years ago, and 11 were taken to other parts of the churchyard to be laid by the side of their dead relatives. During the whole time the Marquis of Londonderry, who is suffering badly from gout, sat in the churchyard, surrounded by members of his family.

It was 6 o’clock before the last rites of the Church were performed, and then the large crowds quietly dispersed. The pitmen of the district, though they have a rough exterior, are undoubtedly a fine body of men, and their quiet demeanour showed that they were touched by the calamity which comes directly home to them. There was no rushing or crowding around the graves, and within a few minutes of the closing ceremony there were not a hundred people visible.

SUNDAY NIGHT 11 O’CLOCK

Explorations in No. 3 pit are still suspended, but the official reports are that the freshness of the air in the pit is improving. The work at No. 2 shaft is proceeding steadily. A barrier has been erected, and warning has been given that no naked light is to be carried near the mouth of the pit. Another of the bodies which remained unidentified up to this morning has been recognized as that of Thomas Alexander, who leaves a widow and four children. The only means of recognition were the shoes which he was wearing. The remaining body has been identified as that of Joseph Chapman, living in Hall Street, who leaves a wife and four children.

Yesterday, at the morning service in York Minster, Canon Fleming, in the course of his eloquent sermon, said:-

“There is something in the human heart that always must admire courage wherever it is found. We all know as Englishmen that much of England’s greatness has been won for her by the courage of her sons. Last week we heard with pride of the resistless courage of our army in India, which achieved so decisive, a victory with comparatively so small a loss; nor must we omit from the roll of heroism those brave fellows who win for us so many of our material comforts by the constant risk of their own lives. The Seaham Colliery loss vividly proved that fact to us on Wednesday last.

Many a battlefield numbers less dead than one of those explosions, and he must have lost his humanity who can read or hear such tidings without a pang, or who forgets the value which the Bible has stamped upon a single human life, I will make a man more precious than fine gold; even a man than the golden wedge of Ophir, Standing in the pulpit of our Minster, from which words ought to be able to go forth into England, and remembering that next year the first association in the world for the advancement of science will come back to York, its birthplace. I ask can anything more be done by science to make man more precious than the gold which he wins for others to spend. True, we have the safety lamp and other appliances science has given to us, but whether from their imperfectness or from the reckless fault of those who use them – judging by results – we are compelled to admit that the present means employed to preserve human life, whether in our mines or on our railways, are entirely inadequate.

On the latter point our gracious Queen has lately spoken not a moment too soon, and in her own practical way has intimated that she expects deeds not words. Much has no doubt been done in the past but much more remains to be done. Christianity surely bids us all to take care of others as watchfully as we do of ourselves, and the science which is ever wringing some fresh secret out of nature for us should add to its triumphs another chapter. I ask you in this metropolis of the north, so far as lies in your power, not to allow this matter to slip, for I hold it to be one of the many functions of the pulpit to help to quicken the pulse of public opinion on any question that can affect the social as well as the spiritual happiness of our nation.”

END

Pages from www.east-durham.co.uk

Seaton Colliery (HIgh Pit), sinking began 1845, coal first produced in 1852, Seaham Colliery (Low Pit) sinking began 1849 a few years later the two collieries were amalgamated (1864)In the first weeks of working at Seaton Colliery there were 3 explosions as 40 years after the invention of the safety lamp, candles were still being used in the pit. In the explosion of 6th of June 1852, 6 men & boys were killed the youngest, Charles Halliday, was officially stated as being 10 years old but was actually aged between 8 years and 2 months and 9 years and 2 months.

Seaton Colliery (HIgh Pit), sinking began 1845, coal first produced in 1852, Seaham Colliery (Low Pit) sinking began 1849 a few years later the two collieries were amalgamated (1864)In the first weeks of working at Seaton Colliery there were 3 explosions as 40 years after the invention of the safety lamp, candles were still being used in the pit. In the explosion of 6th of June 1852, 6 men & boys were killed the youngest, Charles Halliday, was officially stated as being 10 years old but was actually aged between 8 years and 2 months and 9 years and 2 months.